CVC is not Monolithic

The Four Strategic Use Cases for Corporate Venture Capital

Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) has grown considerably over the past ten years. According to Silicon Valley Bank, the number of Corporate VC funds worldwide has expanded to over 4,000, and in 2021 those funds participated in ~26% of all global venture deals. In today’s world, the value of CVC as a strategic tool has never been greater—nor has it been more imperative.

Given these trends, more and more corporations are launching or expanding venturing programs. But we find Executive teams often approach corporate venturing too narrowly. CVC is a powerful tool to not only earn financial returns, but to accelerate innovation, build ecosystems, and drive transformative business growth. CVC is not monolithic; it’s multi-dimensional, with four main strategic use cases. The following is a framework to help establish which kinds of CVC program(s) are right for your company.

The Four Strategic Use Cases

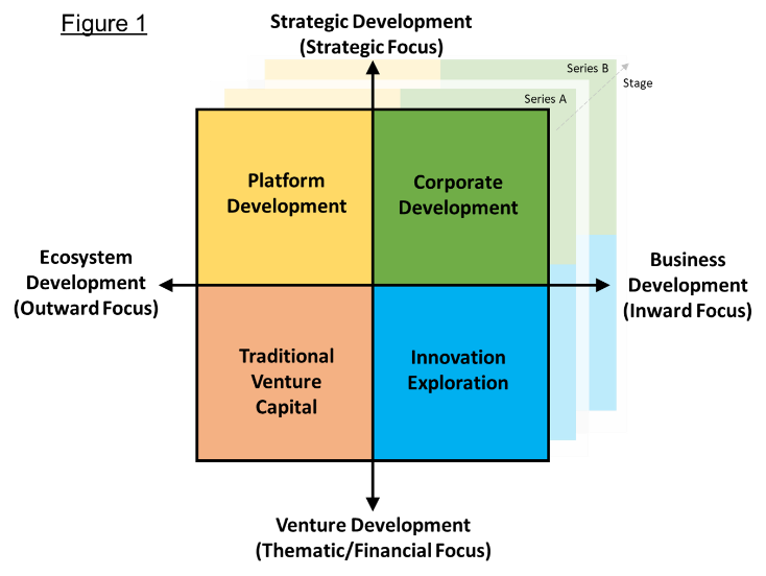

A simple way to think about the various strategic use cases is to consider where to focus efforts along two dimensions:

- A focus on strategic-first returns versus financial-first returns (Financial returns are defined as a corporation’s share of the value of a venture and strategic returns are defined as the value the corporate can itself create because of a venture)

- A focus on the corporation’s business model (internal growth & optimization) versus external ecosystem development (outward on partnerships, collaborators).

Together, these dimensions frame four different use cases, each meant to target a different strategic outcome (Figure 1).

Answers to these choices do not need to be binary (i.e., you can target both strategic and financial returns), but the selections a corporation makes reveal where, and why, a corporation should be using venturing.

Traditional Venture Capital

A commonly understood use case is to follow the traditional venture capital model. Here, the corporation plays the role of objective thematic investor, investing in ventures where it has a proprietary ability to make sensible financial investment decisions (due to deep industry expertise) and where it could add value to a venture as it scales. The corporation has no explicit strategic business goals for the ventures it backs, nor does it expect to leverage the technologies or solutions from these ventures; the focus is on fostering the growth & development of the ventures to make an optimal financial return. Some corporations operating in this quadrant believe they have a role to play in developing the industry around them and/or to support the evolution of the industry to a better place—regardless of whether it directly benefits the economics of the corporation (Impact investing is an example of this.)

Corporations operating here prioritize financial returns from investments and measure success in terms of the number of ventures that achieve financial return hurdle rates.

Innovation Exploration

The second use case focuses on exploring and learning from emerging innovation to inform and shape corporate strategy. Here, the Corporation seeks to identify, catalyze and help direct technologies/solutions it believes may, one day, be consequential to its business. The corporation invests thematically, but here its investment decisions are more intentional around themes grounded in the kinds of technologies it believes may future-proof its businesses. Corporations operating in this space recognize there is value in leveraging investment to establish and position venture relationships to exploit in the future.

Corporations pursuing this use case are seeking to achieve several strategic objectives:

- Awareness/Learning: Programs give corporations early insights into transformation technologies and solutions emerging in relevant market space

- Influence: Programs enable corporations to establish relationships with ventures in order to influence the direction and trajectory of new technologies

- Access: Programs enable corporations to establish strategic footholds early and often to potentially leverage later

Corporations seek strong (or moderate) financial returns in the short term (and explicitly acknowledge that some investments will not pay off). But they also expect some investments to potentially generate strategic returns in the future. Success is measured by the value of strategic insight, financial returns, and the number of ventures that develop into successful new solutions for the industry.

Corporate Development

The third use case leverages venture investing to explicitly unlock new profitable business growth. Here, corporations view venturing as a highly strategic supplement to (and, often, a replacement for) internal innovation and as well as a supplement to and potential feeder for M&A. As such, corporations pursuing this use case recognize venturing as another critical tool to add new products to its offerings, acquire new technologies, create new business platforms, and engineer new business models. Corporations have a healthy expectation for financial returns, but there is a far greater expectation for strategic returns (i.e., new revenue or profit) based on how venture relationships can drive new efficiencies, business model transformation, growth, and new market entry.

Corporations pursue this use case because they believe that without it, they will not be able to keep pace with competition or the evolution of the market. Success is measured by the number of ventures that are productively leveraged to achieve the corporation’s strategies and the new revenue/profit created as a result.

Platform Development

The fourth use case addresses a special situation where corporations seek to create ecosystems of new venture businesses that can expand the value of corporate platform(s). Most corporations pursuing this use case operate platform-based business models (The Alexa voice-enabled solution platform is a good example). Because platforms are usually proprietary, it makes sense for a corporation to want some control of the platform’s ecosystem development by actively seeding and supporting new ventures to grow up and flourish around it. Investment decisions are intentional. The platform ecosystem is built up of ventures the corporation believes will both leverage its business platforms and expand the platform’s value.

Corporations have a modest-to-high expectation for financial returns and a strong expectation for strategic returns. Success is measured by the number of ventures that grow into productive contributors to the platform’s ecosystem.

Strategic Use Cases in Action

Here are four examples of how existing corporate venture capital funds have approached these use cases (Figure 2). Each of these companies chose to pursue venturing differently with different expected outcomes. Although some corporations may choose to pursue a single-use case; corporations are increasingly electing to pursue several use cases, simultaneously.

Google Ventures (GV) is an example of a fund running the Traditional Venture Capital play. GV operates as a return-driven fund, making thematic investments across Enterprise, Life Sciences, Consumer, and frontier technologies. “GV backs founders who transform industries and create new ones.” There may be many reasons why GV is approaching venturing in this way—but an important one is the excess capital of Alphabet.

Citi Ventures, by contrast, plays at the other end of the spectrum. Its focus primarily spans the Corporate Development and Innovation Exploration plays with an explicit objective to leverage venture investing in improving its businesses: “Citi Ventures invests in category-defining startups with the potential to augment and enhance Citi’s products and services.” It makes good strategic sense for Citi to be pursuing corporate venturing in this way. The pace of innovation and technology evolution in the financial sector involves such new technologies (e.g., blockchain) and is moving at such a speed that Citi has determined the best way to evolve its own business is to leverage external innovation actively.

Two other CVC funds illustrate venture efforts focused on Platform Development. Amazon Alexa is a platform-based business for the Alexa voice-enabled platform. For this platform to flourish, Amazon must attract third-party innovators to build applications that run on Alexa and extend/expand the platform’s value. The Amazon Alexa Fund actively invests in and works with “founders who are trailblazers in their fields…[helping them] navigate Amazon and innovate with Alexa.” Salesforce is another kind of ecosystem example. Salesforce is an enterprise software company that cultivates ventures to help it make the core software better and to create applications that may use, and run on its software platforms. Salesforce’s venture effort is “focused on creating the world’s largest ecosystem of enterprise cloud companies.” By investing in startups that use its platform, Salesforce not only expands its platform but creates new customers for itself.

Moving Forward

CVC is a powerful, multi-dimensional executional tool for corporations. Depending on strategic goals—and the opportunity afforded by venture collaboration—corporations may pursue CVC to achieve many different objectives. Some corporations elect to focus on one quadrant while others, work across several. A corporation with many business units may pursue Innovation Exploration for one business and Platform Development for another. The key is to understand strategic objectives—and how venturing can augment or accelerate progress toward those objectives.

In the end, the corporations that achieve the greatest success will recognize CVC is not monolithic and will pursue the set of use cases that best align with their strategies and market opportunities.

About the Author: Andrew Annacone has led a multi-faceted career as a venture capitalist, strategic advisor, startup founder, and corporate executive; Andrew is Managing Partner at TechNexus Venture Collaborative and President at Podfund. He believes in the power of innovation and technology to enable new business models for business—and society.

Author’s Note: Though I do not discuss it in detail here, the use case(s) a corporation elects to pursue also determines how it designs the programs and organizational infrastructures to support its venturing efforts. Everything from the size of the fund to the target venture investment stage (Seed, Series A, Series B), check size, follow-on investment strategy, internal team allocation, nature of venture collaboration efforts, and program management are determined by which use case(s) the corporation pursues. Pursuit of “Innovation Exploration,” for example, may (though not always) focus entirely on seed-stage ventures with small investment checks and collaboration based on learning exchange. By contrast, “Corporate Development” may involve a substantial proportion of mid-to-late-stage venture investments (alongside some early-stage investments), larger checks overall, deeper collaboration toward well-defined synergistic objectives, and strong involvement with business units. These factors influence the scope, scale, nature, and governance of CVC programs.

TechNexus helps leading corporations and entrepreneurs partner with each other to grow revenue, create new business models, and increase market share by discovering previously unseen threats, creating valuable partnerships, or taking advantage of investment opportunities.